NEXT STORY

The cautionary tale of James Raventos

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The cautionary tale of James Raventos

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. My journey from a mining community to a scholarship at St Andrews | 3 | 702 | 06:00 |

| 2. Highlights of the St Andrews and Dundee Medical Schools | 305 | 04:10 | |

| 3. A year in the physiology department at St Andrews | 1 | 257 | 02:57 |

| 4. Working in Singapore | 281 | 04:01 | |

| 5. Setting up a physiology department at Glasgow Veterinary College | 213 | 02:42 | |

| 6. Developing the idea of a beta receptor antagonist | 2 | 414 | 06:53 |

| 7. Working in the dream world of Imperial Chemical Industries | 299 | 03:41 | |

| 8. The accident that led to beta blockers | 3 | 978 | 05:31 |

| 9. The cautionary tale of James Raventos | 1 | 301 | 01:28 |

| 10. Simulating fear in patients | 254 | 04:14 |

The accident was that here I wanted to stop adrenaline acting on the heart and here is the drug. So adrenaline to isoprenaline is just a methyl group being replaced by an isopropyl group. And so isoprenaline selectively stimulates the heart and dilates the bronchi, and that's all we knew. So, where do you start to go looking for an antagonist? So, all we could think of starting was with isoprenaline. Now, I had read a paper somewhere that you could make an antagonist out of a molecule, par doublement la molecule – doubling it up – so that's what we set out to do: to make doubled up versions of isoprenaline. So, basically, these are dibenzyl ethylamines. So, that's... we were working away with these, and getting nowhere in finding an antagonist. And then... so, let me tell you, isoprenaline, it is derived from an amino acid and it's of the phenyl group and the side chain and amine group. Two hydroxyl groups on the ring, so it's a dihydroxy. And it was known, by this time, that the action of adrenaline was terminated by one of these hydroxyl groups becoming methylated. And so a group out in Eli Lilly, in the States, were trying to make a long acting version of isoprenaline, and so they thought: it's these hydroxyl groups that are metabolically labile... let's replace them with something. So, they replaced them with two chlorine atoms, dichloro analogue of isoprenaline. Well, they tested it. It had ceased to be a bronchodilator, so they hadn't achieved their objective. But they did notice that once a preparation had been treated with DCI, as it's called – dichlorides or DCI – that it would no longer respond to isoprenaline. Now they didn't know about Ahlquist's work and so when they published the work they didn't talk about maybe this was blocking beta receptors, but it was published, and two months later... that was published at the end of... just about... end of about '58, beginning of '59, and two months later a paper appeared from a group down in Atlanta claiming that, in fact, the stuff was acting by blocking Ray Ahlquist's beta receptors. So, was this the lead we were looking for? So, John immediately made it, and we tested it, and in the preparation we were using, it was just as though we'd given isoprenaline. So at that time my knowledge of pharmacology was pretty well non-existent, so I didn't understand it; put it on the side. And then we went ahead. Now John, when he looked at this, pointed out to me that these chlorine atoms were quite large, and so big lipophilic... he said, 'You know, if... if I joined up two phenyl groups it would be the, sort of, same shape and size, so that's going from... to analine'. But, in the meantime, I had changed my method of assessing these compounds and found that, in this new preparation, that DCI wasn't... didn't have these isoprenaline-like agonist activity. And so suddenly we got all excited about DCI. John had this idea about analine so that was the first. I remember, from idea to making it, to it working, that's my recollection. I mean, and by Jove, we got something which was as good as DCI but without any agonist activities. So, and that was the first beta blocker and we went into man with it. It came from Alderley Park, so it was Alderlin. Do you remember? Pronethalol. Pronethalol, yes. But we learned a lot from that compound. Then, subsequently a better compound was made when we... By this time ICI, you see, had woken up to the possibility that maybe there was some money here, and put a whole bunch of chemists on with... Bert Krause, I remember, was the leader of this group and so they did a great job at ordering in the changes, and they produced propranolol, and that has been the backbone of beta blocking drugs ever since.

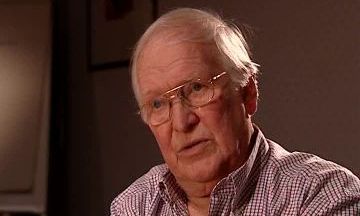

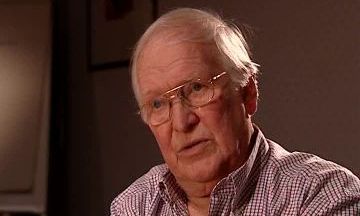

The late Scottish pharmacologist Sir James W Black (1924-2010) revolutionised medical treatment of hypertension and angina with his invention of propranolol, the first ever beta blocker. This and his synthesis of cimetidine, used for the treatment of peptic ulcers, earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1988.

Title: The accident that led to beta blockers

Listeners: William Duncan

After graduating with a BSc Bill Duncan went on to gain a PhD from Edinburgh University in 1956. He joined the Pharmaceuticals Division of ICI where he contributed to the development of a number of drugs. In 1958, he started a collaboration with Jim Black working on beta blockers and left ICI with him in 1963 to join the Research Institute of Smith Kline & French as Head of Biochemistry. He collaborated closely with Black on the H2 antagonist programme and this work continued when, in 1968, Duncan was appointed the Director of the Research Institute. In 1979, he moved back to ICI as Deputy Chairman (Technical), a post he occupied until 1986 when he became Chairman and CEO of Coopers Animal Health. He ‘retired’ in 1989 but his retirement was short-lived and he held a number of directorships in venture capital backed companies. One of his part-time activities was membership of the Bioscience Advisory Board of Johnson and Johnson who asked him to become Chairman of the Pharmaceutical Research Institute of Johnson and Johnson in New Jersey. For personal reasons he returned to the UK in 1999, but was retained by Johnson and Johnson until 2006 in a number of senior position in R&D working from the UK. From 1999 to 2007 he was a non-executive director of the James Black Foundation. He is now fully retired.

Tags: Alderley Park, Raymond Ahlquist, Bert Krause

Duration: 5 minutes, 31 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2006

Date story went live: 02 June 2008