NEXT STORY

Actively repairing watches while in the army

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Actively repairing watches while in the army

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Aborting the flight to Egypt | 1 | 1493 | 00:59 |

| 12. Army service in Egypt and Palestine | 1557 | 04:58 | |

| 13. Actively repairing watches while in the army | 1973 | 01:26 | |

| 14. Moving from watch repairer to watchmaker | 2228 | 04:45 | |

| 15. Evening classes in horology were not beneficial | 1995 | 02:19 | |

| 16. Enjoying the experience of learning | 1913 | 01:06 | |

| 17. I didn't have any friends in horology | 2129 | 01:44 | |

| 18. My partner drank all the profits | 2076 | 00:40 | |

| 19. My Bentley exuded quality | 1977 | 05:27 | |

| 20. Sam Clutton introduced me to the upper echelons of horology | 2339 | 03:41 |

There we were. We landed at Toulouse and fixed the engine. And having done that, we trundled out for take off again and found we'd got a broken undercarriage. So we all trundled out again to get the undercarriage repaired and took another two days, and these planes were all worn out. They'd been on service for four years during the war. And so fine, we got airborne and got to Egypt near Cairo. And these planes were unbelievably noisy. I mean there is a huge roaring like an express train, continuously throughout the journey, and when we got out in Egypt, the silence was impenetrable. It was like a huge, black velvet cover had gone over everything, not a sound to be heard. Absolutely silent. We were all half deaf, you see. And then there was the heat and an amazing number of things going on. Labour was plentiful. Egyptian... the Egyptian fellaheen they call the Egyptian labourers, and they get treated very badly and they do all the work and you don't have to lift a finger, everything is done for you.

And I spent a year or so in Egypt. It wasn't very interesting. On one occasion I had decided not to go on a physical training exercise, which was quite illegal, because I wanted to repair this watch, because I was doing a bit of watch repairing. And half an hour after the platoon went off to do their exercises, in came the sergeant major and I thought well I'm for the high jump now, he's got me well and truly. And he said to me that the company commander wanted to see me, and I thought well this can be big stuff, I'm really going to get rained on here. And so I went to the commander officer, and 'Now Daniels', he said, 'I understand you can type'. 'Oh yes sir', I said. I'd never been nearer to a typewriter than my headmaster's old machine at school, but it wouldn't do to say you couldn't type, after all, typing is a terribly easy thing to do, all you've got to do is push the buttons down. So I said yes, I could type. Well he said, then report here tomorrow morning at 9 o'clock and take over the duties of company clerk.

It was a wonderful plum job. You know, I mean, I was excused from everything. No more parades, no more guard duties, no more drill, just company commander's clerk. And as a company commander's clerk, you practically run the company, you know, with the routine and you just organise it all each day. So that was very beneficial to me and the second time in my life I'd got out of an awkward situation... an un-likeable situation, first from my mattress days and now here in the army. So I was very happy with my position as it stood at that moment.

Then we went to Israel and Palestine, and we crossed the Sinai Desert, which is a major experience in one's life to do that, on wheels across the desert. The desert looks lifeless, but it teems with life. You know, you just scrape the sand aside and there is something alive there, and especially lizards, small lizards who lose their tails, if you grab them by their tail they shake off their tail and go. And we ran into some difficulties in Palestine because of the Stern Gang, and so we had to be very alert and it could be quite dangerous, but if you, you know, took normal precautions it was all right. And we moved on up to Haifa with a beautiful climate and we camped on the edge of the sea and spent all day swimming. It was wonderful, and all paid for by the taxpayers, and terribly extravagant. When we wanted to go to a football match, there might be six or seven of us wanting to go to a football match, then we'd all pile into one of these giant transporters that could hold two tanks and 50 people and it's doing one and a half miles to the gallon and we go off for a 15 mile run just to watch a football game. So it was all frightfully extravagant, but well that's the way the army works.

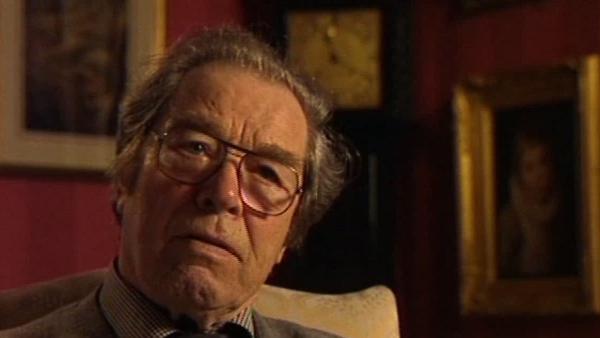

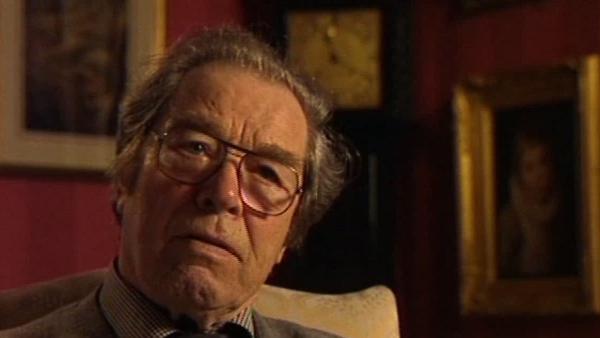

George Daniels, CBE, DSc, FBHI, FSA (19 August 1926 - 21 October 2011) was an English watchmaker most famous for creating the co-axial escapement. Daniels was one of the few modern watchmakers who could create a complete watch by hand, including the case and dial. He was a former Master of the Clockmakers' Company of London and had been awarded their Gold Medal, a rare honour, as well as the Gold Medal of the British Horological Institute, the Gold Medal of the City of London and the Kullberg Medal of the Stockholm Watchmakers’ Guild.

Title: Army service in Egypt and Palestine

Listeners: Roger Smith

Roger Smith was born in 1970 in Bolton, Lancashire. He began training as a watchmaker at the age of 16 at the Manchester School of Horology and in 1989 won the British Horological Institute Bronze Medal. His first hand made watch, made between 1991 and 1998, was inspired by George Daniels' book "Watchmaking" and was created while Smith was working as a self-employed watch repairer and maker. His second was made after he had shown Dr Daniels the first, and in 1998 Daniels invited him to work with him on the creation of the 'Millennium Watches', a series of hand made wrist watches using the Daniels co-axial escapement produced by Omega. Roger Smith now lives and works on the Isle of Man, and is considered the finest watchmaker of his generation.

Tags: Toulouse, Egypt, Cairo, Israel, Palestine, Sinai Desert, Haifa, Stern Gang, Fellaheen

Duration: 4 minutes, 59 seconds

Date story recorded: May 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008