NEXT STORY

Enjoying the experience of learning

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Enjoying the experience of learning

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Aborting the flight to Egypt | 1 | 1493 | 00:59 |

| 12. Army service in Egypt and Palestine | 1557 | 04:58 | |

| 13. Actively repairing watches while in the army | 1973 | 01:26 | |

| 14. Moving from watch repairer to watchmaker | 2228 | 04:45 | |

| 15. Evening classes in horology were not beneficial | 1995 | 02:19 | |

| 16. Enjoying the experience of learning | 1913 | 01:06 | |

| 17. I didn't have any friends in horology | 2129 | 01:44 | |

| 18. My partner drank all the profits | 2076 | 00:40 | |

| 19. My Bentley exuded quality | 1977 | 05:27 | |

| 20. Sam Clutton introduced me to the upper echelons of horology | 2339 | 03:41 |

So I set myself the task of learning more when I came home on leave. I bought books, studied the books, tools, equipment and did very well and came out of the army with a sufficient sum of money to be able to take a job as rather a poor professional watchmaker, but knowing enough to get by. And I was taken on, fortunately. The pay was only £3 a week, but indeed, it was so inadequate that after a while I was obliged to sell my own wristwatch to make up the rent for my digs. But I went to evening classes and studied hard on the theory of horology, which most practising horologists don't have very much time for, but it is very important if one is to get an overall picture of the whole science of the thing, very important to do that. And so I studied, not very enthusiastically, but I knew it had to be done and I wanted to get through the exams. And in a practical way, from a practical point of view, the evening classes weren't very beneficial. I didn't learn anything about horology, excepting the theory of horology, and even at one stage, when I was actually doing professionally more highly-skilled work than we were doing at evening classes, I was accused of having got someone else to make my exercise pieces. I'm very flattered they were so good that they thought I hadn't made them, but it wasn't a very enjoyable experience, and fortunately I was able to show that I had done it. So, it was a two-edged sword. On the one hand, I was pleased that I could work to that standard, on the other hand I was disappointed and disillusioned with evening classes because that was the beginning of my experience of the closed shop mentality of the average horologist, who if you were good, wouldn't say so, and if you weren't very good he was very pleased to point out your shortcomings.

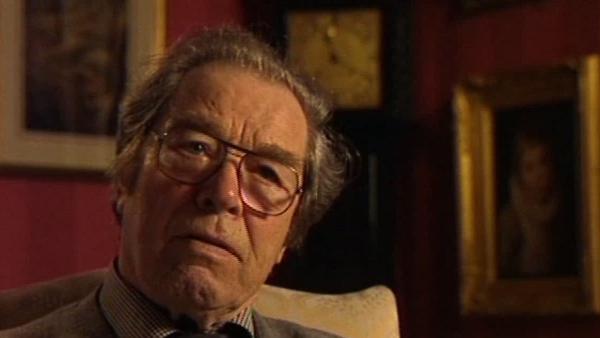

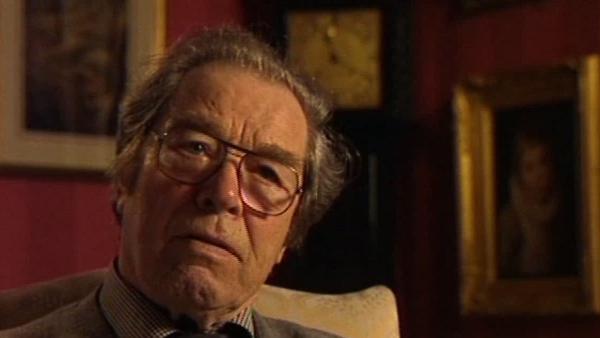

George Daniels, CBE, DSc, FBHI, FSA (19 August 1926 - 21 October 2011) was an English watchmaker most famous for creating the co-axial escapement. Daniels was one of the few modern watchmakers who could create a complete watch by hand, including the case and dial. He was a former Master of the Clockmakers' Company of London and had been awarded their Gold Medal, a rare honour, as well as the Gold Medal of the British Horological Institute, the Gold Medal of the City of London and the Kullberg Medal of the Stockholm Watchmakers’ Guild.

Title: Evening classes in horology were not beneficial

Listeners: Roger Smith

Roger Smith was born in 1970 in Bolton, Lancashire. He began training as a watchmaker at the age of 16 at the Manchester School of Horology and in 1989 won the British Horological Institute Bronze Medal. His first hand made watch, made between 1991 and 1998, was inspired by George Daniels' book "Watchmaking" and was created while Smith was working as a self-employed watch repairer and maker. His second was made after he had shown Dr Daniels the first, and in 1998 Daniels invited him to work with him on the creation of the 'Millennium Watches', a series of hand made wrist watches using the Daniels co-axial escapement produced by Omega. Roger Smith now lives and works on the Isle of Man, and is considered the finest watchmaker of his generation.

Tags: British Army

Duration: 2 minutes, 20 seconds

Date story recorded: May 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008