NEXT STORY

Evening classes in horology were not beneficial

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Evening classes in horology were not beneficial

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Aborting the flight to Egypt | 1 | 1493 | 00:59 |

| 12. Army service in Egypt and Palestine | 1557 | 04:58 | |

| 13. Actively repairing watches while in the army | 1973 | 01:26 | |

| 14. Moving from watch repairer to watchmaker | 2228 | 04:45 | |

| 15. Evening classes in horology were not beneficial | 1995 | 02:19 | |

| 16. Enjoying the experience of learning | 1913 | 01:06 | |

| 17. I didn't have any friends in horology | 2129 | 01:44 | |

| 18. My partner drank all the profits | 2076 | 00:40 | |

| 19. My Bentley exuded quality | 1977 | 05:27 | |

| 20. Sam Clutton introduced me to the upper echelons of horology | 2339 | 03:41 |

I was demobbed in November '47, and I'd been three years in a hot climate and I came back to England and it was the worst winter we'd had for 15 years and the whole of England was icebound and the only clothes I had were my demob clothes, my Burton 50 shilling suits and a waterproof coat.

And what to do now? I wanted to be a watch repairer and I knew I didn't have really enough experience, but in Edgware in North London, I had while I'd been on leave and looking for tools and information met a man who was himself just demobbed from the army and he ran the watch repair side of the jewellers in Edgware. And I had spoken to him and he'd seen my watch and he asked me who made the glass for it. It was very complex glass, which I'd made from Perspex. I mean when you're in the desert, you know, you can spend months just shaping a bit of plastic. You've got nothing else to do, and so I did all that and made various bits for the watch and he was very impressed, and I spoke... having read De Carle, and I spoke with great authority about how certain things were done. And he suggested I came back to see him when I came out. And so I did and he gave me a job and I've never been so lucky in my life to get that job. And it was £3 a week and my digs, my accommodation were £2.50 a week, so there was 50p left over to live on, after I had paid my digs. And so I was forever scrabbling round trying to make enough money to live on, get a watch and repair it and sell it, and of course watches were in very short supply. You weren't allowed to import them. They were hard to obtain and there didn't seem to be very many good watchmakers about to repair them, so one way or another, it was all very helpful to me. So I became a trade watch repairer.

It never occurred to me that that was not what I should be aiming for. I was very lucky to be in work and working at what I liked and I really enjoyed that and I knew I was working at what I liked so I was prepared to go to quite a lot of trouble. But the money was totally inadequate and so I had joined up with the Northampton Polytechnic, evening classes and there met a man who said his employer was looking for a watchmaker. So instantly in my mind I became a very advanced, superior watchmaker and I would go along to be interviewed and I'd bought a lot of tools. In fact, when this man interviewed me, I discovered I'd got more tools than he had. I mean I'd got lathes and everything, and so he was very impressed by that and he very foolishly let me know how impressed he was because I had all this equipment. So when it came to negotiating the salary, I pointed out that, you know, the £8 a week I was earning at the moment was really somewhat inadequate and I really ought to do something about it and that's the reason I'm prepared to change my situation. And he said to me, 'Well all right then, £9 a week'. I was so ecstatic that I couldn't think of an answer and he's thinking that I was delaying and he said, 'Well all right then, and another 10 shillings travelling expenses'.

So, of course, I had to agree, and so suddenly I went into the millionaire bracket and I could buy clothes. I mean I had holes in my shoes and I could buy clothes and a motorbike so that I could move about more freely. And I'd go up to Northampton Polytechnic every day on the motorbike and then motorcycle on to Edgware where I was in digs, and that is 25 miles between Croydon, where I worked, and Edgware where I lived. And I'd have to do that every day, starting at 5:30 in the morning, from Edgware to Croydon to get there at seven. And then in the evening, up to evening classes and not home then till 11.

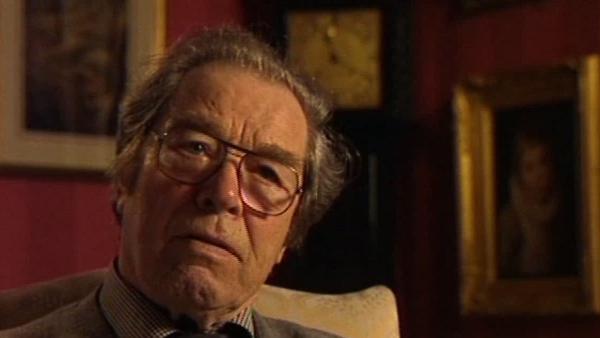

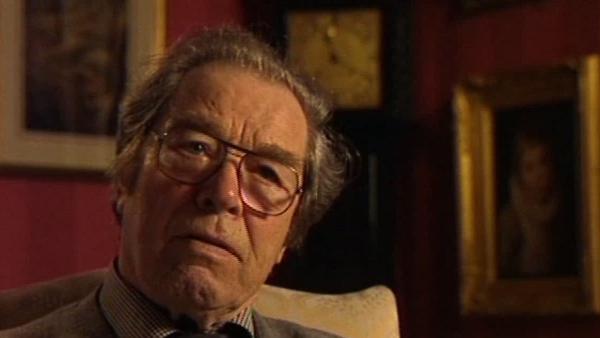

George Daniels, CBE, DSc, FBHI, FSA (19 August 1926 - 21 October 2011) was an English watchmaker most famous for creating the co-axial escapement. Daniels was one of the few modern watchmakers who could create a complete watch by hand, including the case and dial. He was a former Master of the Clockmakers' Company of London and had been awarded their Gold Medal, a rare honour, as well as the Gold Medal of the British Horological Institute, the Gold Medal of the City of London and the Kullberg Medal of the Stockholm Watchmakers’ Guild.

Title: Moving from watch repairer to watchmaker

Listeners: Roger Smith

Roger Smith was born in 1970 in Bolton, Lancashire. He began training as a watchmaker at the age of 16 at the Manchester School of Horology and in 1989 won the British Horological Institute Bronze Medal. His first hand made watch, made between 1991 and 1998, was inspired by George Daniels' book "Watchmaking" and was created while Smith was working as a self-employed watch repairer and maker. His second was made after he had shown Dr Daniels the first, and in 1998 Daniels invited him to work with him on the creation of the 'Millennium Watches', a series of hand made wrist watches using the Daniels co-axial escapement produced by Omega. Roger Smith now lives and works on the Isle of Man, and is considered the finest watchmaker of his generation.

Tags: Northampton Polytechnic, Burton (retailer), Perspex, Donald De Carle

Duration: 4 minutes, 46 seconds

Date story recorded: May 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008