NEXT STORY

Beginnings of Polish cinematography

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Beginnings of Polish cinematography

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. First experience of film-making - working with Aleksander Ford | 93 | 05:26 | |

| 32. School of Fine Arts helped me to become an artist | 56 | 04:53 | |

| 33. Farewell, film school | 70 | 02:35 | |

| 34. Ideology in A Generation | 96 | 05:00 | |

| 35. Jan Matejko's heritage | 77 | 04:01 | |

| 36. 'We had literature, we had painting and we had Jan Matejko' | 53 | 03:26 | |

| 37. Pre-war versus post-war cinema | 71 | 03:07 | |

| 38. Beginnings of Polish cinematography | 80 | 03:04 | |

| 39. Freedom in Polish cinematography | 68 | 04:38 | |

| 40. Loyalty to subordinates | 55 | 05:08 |

Może warto powiedzieć, jakie było nasze samopoczucie jako ludzi, którzy przyszli do Szkoły Filmowej i stanęli właśnie przed tym wspaniałym urządzeniem, jakim była kamera filmowa i, że tak powiem, mieli się zmierzyć z nowym zupełnie zadaniem stworzenia polskiego kina powojennego. Jedno wiedzieliśmy wszyscy – że kino przedwojenne jest naszym śmiertelnym wrogiem. Nie było niczego, czego nienawidzilibyśmy bardziej i pod tym względem myślę, że cała nasza szkoła razem z naszymi profesorami była tego samego zdania. Przedwojenne kino albo było ckliwo-patriotyczno-religijne, albo było skrajnie komercjalne. I dwa powiedzenia producentów filmowych przedwojennych pamiętam. Jeden z nich mówił tak: 'Ja nie robię filmów, proszę wstać'. A film Proszę wstać to był film o tematyce patriotycznej. I w pewnym momencie ktoś się zrywał i śpiewał narodową pieśń i wtedy Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła, Pierwsza Brygada i wtedy cała widownia musiała wstać. Więc on mówił: 'Ja nie robię filmów, proszę wstać'. Ale i byli inni producenci, którzy z kolei mieli taką zasadę – mówili: 'Ja nie robię filmów klamkowych'. O co chodziło? Że mówi: 'Tu mi reżyser robi, tu mi pisze... z jednych drzwi wchodzą w drugie, znowu jakieś drzwi' – mówi – 'ile dekoracji musiałbym wybudować? Co to, klamkowy film? Otwierają drzwi jedne po drugich!' Mówi: 'Ile to mnie będzie kosztować?' W związku z tym Adolf Dymsza, wielki komik polskiego, przedwojennego filmu opowiadał mi jak to dekoracja była wybudowana w małym studio na czwartym piętrze, tak blisko były drzwi, że on nie mógł z rozmachem przez te drzwi... ściany, a właściwie okna... że on nie mógł z rozmachem wejść do dekoracji. Więc mówi: 'Na tym czwartym piętrze otworzyłem okno, które było tuż naprzeciw tych drzwi, żeby mieć rozpęd' – mówi. 'I z tego otwartego okna tam cztery piętra w dół' – mówi. 'Ja skoczyłem i otworzyłem energicznie drzwi do dekoracji'. To pokazuje jak te filmy były robione za małe pieniądze, jak one były, po prostu, taką beznadziejną manufakturą. No już nie mówiąc o treści tych filmów, które były po prostu imitacją przede wszystkim niemieckiej produkcji rozrywkowej. Tak że to wiedzieliśmy, że za naszymi plecami nie ma nikogo. My byliśmy pierwsi. I myślę, że Andrzej Munk miał takie poczucie, że i Kawalerowicz miał takie poczucie, zaczynając robić filmy, i Stanisław Różewicz. My wszyscy czuliśmy, że tam nic... My – wszystko jest przed nami.

Perhaps it's worth mentioning what we felt like as people who had come to the film school and who were confronted with this amazing contraption, the film camera, and had to measure up to the completely new task of creating post-war cinema in Poland. There was one thing we all knew, which was that pre-war cinema was our mortal enemy. There was nothing that we hated more, and in this respect, I believe that everyone in our school together with the tutors felt the same way. Pre-war cinema was either sentimentally patriotically religious, or else it was commercial in the extreme. I remember the sayings of two pre-war film producers. One of them used to say, I don't make 'Please all rise' films. A 'Please all rise' film was about patriotic things, and during the course of the film, someone would leap to their feet and start singing a nationalist song like Poland hasn't fallen yet or The First Brigade and then everyone in the audience had to rise. So this producer would say, 'I don't make 'Please all rise' films.' But there were other producers who had different principles. 'I don't make door-knob films.' What was this about? The director tells me, 'The characters are passing through one door into another, how many sets would I have to build? What is this, some kind of 'door-knob' film? They open one door after another!' He says, 'How much is this going to cost me?' Adolf Dymsza, a great comedian in pre-war cinema, told me how the sets had been built in a tiny studio on the fourth floor; the door was so close to the window that he was unable to come onto the set with a flourish. So he says, 'I opened a window on the fourth floor opposite the door so that I could take a run' - he says - 'and jumped from this open window, down four floors so that I could open the door to the set with a flourish.' This shows how those films were made for very little money, how they were just worthless. To say nothing about the storylines of these films; they were copying mainly German entertainment productions. So we knew this much: no one had gone before us. We were the first. I think that Andrzej Munk felt this way, as did Kawalerowicz when he began making films, and so did Stanisław Różewicz. We each felt that there was nothing there. We... everything was before us.

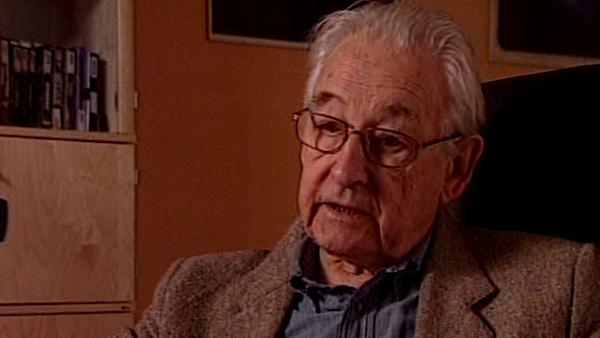

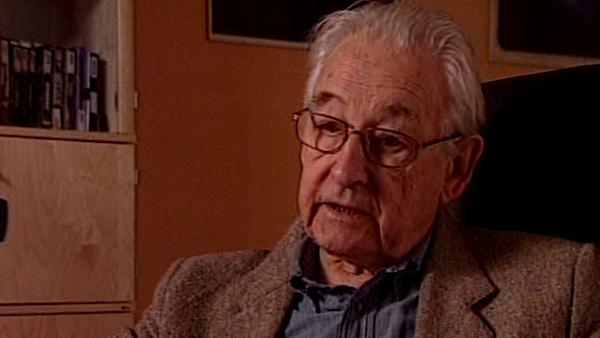

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Pre-war versus post-war cinema

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: Film School, Please All Rise, Poland Has Not Yet Been Lost, The First Brigade, Adolf Dymsza, Andrzej Munk, Stanisław Różewicz

Duration: 3 minutes, 7 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008