NEXT STORY

Loyalty to subordinates

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Loyalty to subordinates

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. First experience of film-making - working with Aleksander Ford | 93 | 05:26 | |

| 32. School of Fine Arts helped me to become an artist | 56 | 04:53 | |

| 33. Farewell, film school | 70 | 02:35 | |

| 34. Ideology in A Generation | 96 | 05:00 | |

| 35. Jan Matejko's heritage | 77 | 04:01 | |

| 36. 'We had literature, we had painting and we had Jan Matejko' | 53 | 03:26 | |

| 37. Pre-war versus post-war cinema | 71 | 03:07 | |

| 38. Beginnings of Polish cinematography | 80 | 03:04 | |

| 39. Freedom in Polish cinematography | 68 | 04:38 | |

| 40. Loyalty to subordinates | 55 | 05:08 |

Nasza kinematografia opierała się na dwóch wielkich indywidualnościach, no, w każdym bądź razie osobowościach: Aleksandra Forda i Wandy Jakubowskiej, która wyszła z Oświęcimia, była przed wojną lewicującą działaczką, zaczęła robić pierwszy film. W związku z tym po jej udanym filmie, jednym z najbardziej udanych pierwszych polskich filmów Ostatni etap, nagle stała się osobą ważną w naszej kinematografii. Wokół tych dwóch indywidualności gromadzili się młodzi ludzie, którzy robili filmy razem z nimi. No, ale była grupa właśnie tych, którzy byli tą grupą, że tak powiem, tym klubem filmowym dyskusyjnym i wśród nich był Jerzy Toeplitz, Antoni Bohdziewicz, był operator Stanisław Wohl i jeszcze kilka osób. I teraz nagle oni doszli do wniosku, że trzeba powołać też do życia Szkołę Filmową. To jest bardzo dziwne, dlatego że w kraju, w którym się robi dwa, trzy filmy, a jest kilku reżyserów w każdym bądź razie, kilku... właściwie ci reżyserzy mogli dojść do wniosku, że nie ma żadnego powodu, nie ma potrzeby, żeby otwierać szkołę w momencie, kiedy nie robi się więcej filmów, jak będziemy robić więcej to otwórzymy szkołę. Nie, właśnie to było zdumiewające, że ci młodzi jeszcze wtedy i pełni energii i pomysłowości filmowcy postanowili otworzyć szkołę dla przyszłości polskiej kinematografii. I to jest, muszę powiedzieć, bardzo taki ważny moment, dlatego że i oni razem z nami jako studentami tej szkoły i oni się uczyli być profesorami. No, Jerzy Toeplitz był bardzo wykształconym człowiekiem, wykładał historię sztuki. Antoni Bohdziewicz był raczej radiowym reżyserem, ale dobrze rozumiał jakby proces powstawania dzieła sztuki i filmu. Stanisław Wohl był bardzo wytrawnym już operatorem po szkole w Paryżu. W związku z tym jego uczniowie, że tak powiem, bardzo szybko opanowali tę trudną sztukę, jaką jest robienie zdjęć do filmu. I tak powstała ta szkoła jako fragment, że tak powiem, kinematografii.

Teraz jest jeszcze jeden bardzo ważny moment, dlatego że często zadają pytanie: no dobrze, ale jak to się stało, że polskie kino miało więcej wolności niż inne? Że w Polsce powstały filmy, które w innych kinematografiach, które były w krajach zajętych przez Sowiety, przez Związek Radziecki, jak Czechosłowacja, Węgry, Rumunia – te filmy były o wiele bardziej ograniczone pod względem cenzuralnym. Otóż nasi koledzy starsi, zwłaszcza Ford i Jakubowska, uważali siebie za działaczy partyjnych i nie chcieli sytuacji, w której ktoś mianowany przez partię jako szef kinematografii miałby ich pouczać co jest słuszne i dobre a co nie, w sensie politycznym. Oni siebie uważali za autorytet w tej sprawie. W związku z tym dążyli od samego początku, żeby stworzyć grupy twórcze, które by były właściwie grupami producentów filmowych, ale na czele tych grup żeby nie stał producent, bo producentem było państwo, tylko żeby stał reżyser. No znaczy w tym wypadku oni wyobrażali sobie, że ta dwójka zupełnie wystarczy i na początku powstały dwa zespoły, dopiero potem one zaczęły się mnożyć. I taka wytworzyła się relacja pomiędzy władzą i pomiędzy nami, jako ludźmi, którzy robią filmy.

Our cinema relied on two great individualities or, at least, personalities: Aleksander Ford and Wanda Jakubowska who had just come out of Auschwitz. Before the war, she had been a left-wing activist and had started making her first film. Because her film The Last Stage was a success, one of the most successful first Polish films, she suddenly became a very important figure in our cinema. Young people gathered around these two individualities to make films with them. But there was also a group of those, who made up this group, this discursive film club, among whom were Jerzy Toeplitz, Antoni Bohdziewicz, the camerman Stanisław Wohl and a few others, and they suddenly came to the conclusion that a film school ought to be set up. This was very odd in a country where two, three films were being made, and there were several film directors who in fact could have come to the conclusion that there was no reason, no need to start a school at a time when more films weren't being made; when we start to make more films, then we'll open a school. No, it was astonishing that these film-makers who were still young and full of energy and ideas decided to start a school for the sake of the future of Polish cinematography. And I have to say that this is a very significant moment because together with us students at this school, they were learning how to teach. Jerzy Toeplitz was a highly educated man, he had lectured on the history of art. Antoni Bohdziewicz was more of a radio director but he had a sound understanding of how a work of art or a film were created. Stanisław Wohl was an expert director of photography who had learned his trade in Paris. Because of this, his students quickly mastered the difficult art of shooting. And this is how the school was set up as a part of our cinematography. There is a second, very important moment since people often ask: how did it happen that the cinema in Poland had more freedom than in other countries, and that in Poland films were made that in other cinematographies in countries occupied by the Soviets, by the Soviet Union, like Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania their films were far more restricted by censors. But our older colleagues, especially Ford and Jakubowska, considered themselves to be Party activists and didn't want a situation in which someone who had been nominated by the Party as the director of cinematography to be lecturing them on what was politically acceptable and what wasn't. They considered that they were already an authority in these matters. Therefore, from the very beginning, they strove to set up creative groups which were actually comprised of film producers but at the head of each of these groups there was a film director not a producer, because the producer was the state. They imagined that these two were quite enough. Initially, there were two teams which later multiplied. And what kind of relationship developed between the authorities and us, the people who were making the films?

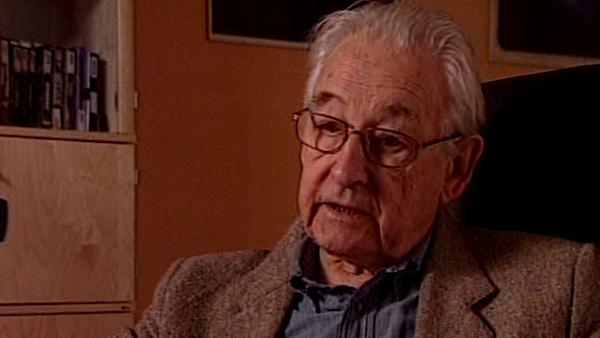

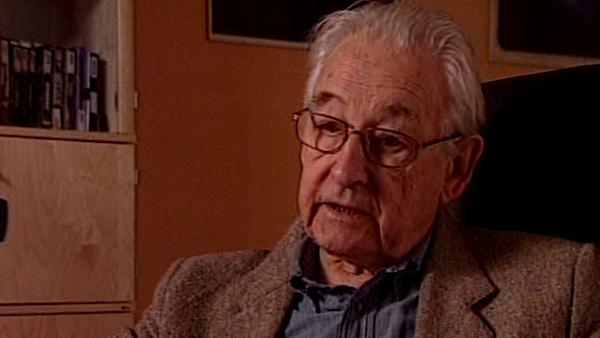

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Freedom in Polish cinematography

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: Auschwitz, The Last Stage, Aleksander Ford, Wanda Jakubowska, Jerzy Toeplitz, Antoni Bohdziewicz, Stanisław Wohl

Duration: 4 minutes, 38 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008